You Can Thank Gladys West for GPS. And, for Connecting Us All to the Stars Beyond

Without GPS, or women like Gladys, we’d all be more lost in this world.

There isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t consult GPS maps for something: scouting out restaurants to meet up for dinner; the closest Starbucks; alternate ways around a traffic jam.

The inventor of GPS has made it easy for so many of us to travel on a whim, navigate an unfamiliar place like a local or tour a city where we don’t speak the language: just pop in your destination and go.

And, it’s settled age-old arguments: no one any longer needs to stop and ask directions.

It’s one of those technologies that we tend to take for granted, or to celebrate the add-ons (hello, Google Map reviews and hours of operation!) more than the foundational science at work underneath it all. And while we may view GPS as priceless, so does Gladys West, whose work became the foundation of the system.

Related: Apple CarPlay and Android Auto: How to Get the Most Popular In-Car Phone Systems

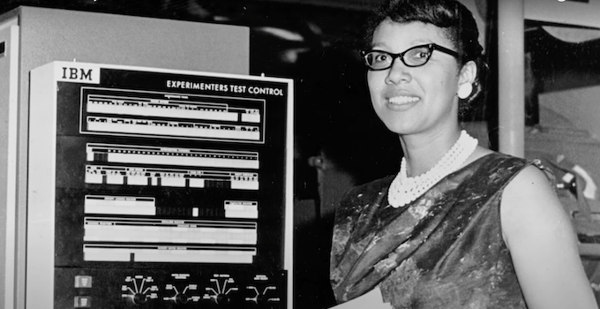

Gladys West, one of the inventors of GPS, at Dahlgren Naval Base. Photo: US Navy

Dreaming Big and Working Hard

Gladys was born on a farm, as a child working alongside her family when she wasn’t in school. But she knew her education would hold promise for her future—including not having to work the land like her parents. But she also knew that she would need help to attend college. She worked to maintain top grades and won a scholarship to Virginia State College, a historically Black college. She majored in math and started her professional life as a teacher before earning a master’s degree in math. In 1956 she was offered a job at the Naval base in Dahlgren, VA where computers were being introduced; her math skills were needed to program the computers and she was hired as a programmer. Her job eventually led to satellite data analysis, creating detailed models of the earth and developing systems to measure the altitude of earth’s terrain, a project on which she became manager. Gladys was smart and fast— and her work alone cut her department’s processing time in half and she was recommended for a commendation in 1979. From there, she continued to refine terrestrial, gravitational and tidal models, all of which eventually became the foundation of GPS, or global positioning system.

Related: 10 Easy (and Affordable) Ways to Add Modern Safety Technology to Your Old Car

Gladys West, was inducted into the Air Force Hall of Fame for her contributions. Photo: US Air Force

A Hidden Figure, Finally Seen

Despite Gladys’s contributions and achievements, her race and gender kept her from being recognized or participating in jobs that would elevate her career further. White male colleagues were invited to travel, write published papers or speak at gatherings, Gladys was not.

In fact, if you Google “GPS inventor,” the first result you’ll get are the names Ivan A, Getting, Bradford Parkinson and Roger L. Easton, her colleagues on the project. But not Gladys West. This is changing though; scan further down the page and you’ll see stories about Gladys and her accomplishments.

While the visibility of her colleagues was certainly unfair, Gladys had her eye on another goal altogether: lighting a path for future women and people of color to advance in math, science and fields traditionally held only by whites. In 2020 she told The Guardian that “her white colleagues were friendly and respectful, but initially didn’t socialise with her outside the office – something she tried not to let get to her. “You know how you know that kind of thing is going on, but you won’t let it take advantage of you? I started to think to myself that I’ll be a role model as the Black me, as West, to be the best I can be, doing my work and getting recognition for my work,” she says.”

As Gladys kept her focus on her job, a revolution was going on outside the doors of her office: The Civil Rights movement was in full force. But, she was a government employee and not allowed to join the protests or risk losing her job. Gladys decided to take her own path to challenging the misperceptions of race and inequality. She told The Guardian that she was “determined to commit herself to her work. She hoped that, by doing it to the best of her ability, she could chip away at the stigma black people faced. “They hadn’t worked with us, they don’t know [Black people] except to work in the homes and yards, and so you gotta show them who you really are,” she explains. “We tried to do our part by being a role model as a black person: be respectful, do your work and contribute while all this is going on.”

Related: What Drives Her: How Diversity—and Equity and Inclusion—Are Changing the Face of the Auto Industry

Ira and Gladys West,one of the inventors of GPS. Photo: The Community Foundation/cfrrr.org

Down To Earth, Despite Astronomical Achievements

Internally on the Naval base, Gladys was increasingly known and recognized for her achievements. But to the outside world she was a wife, mother and Naval employee. That is, until she shared a brief biography with her sorority, Alpha Kappa Alpha, for an alumni event. That ignited wide recognition and in 2018 she was inducted into the United States Air Force Space and Missile Pioneers Hall of Fame, one of the military branch’s highest honors. She’s since earned a number of honors, published an autobiography entitled “It Began with a Dream” and after retiring in 1998, earned a PHd in public and international affairs from Virginia Tech. The Community Foundation named a math scholarship fund for her and her husband, Ira West, who is also a mathematician.

And, she’s still plotting maps, though she prefers paper maps to GPS. “If I can see the road and see where it turns and see where it went, I am more sure,” she told The Guardian. But for the rest of us, we put our confidence in Gladys and the systems she helped create that help us to find our destination, on the road, in life, and beyond.

Gladys West’s contributions are evident in almost all cars these days: GPS-based navigation systems. Photo: IGWest Publishing via Amazon

More About:Car Technology