EV Charging’s Dirty Little Secret — Why It Can Cost As Much As Gas, And How to Pay Less

It takes a bit to figure out the best strategies for EV charging. Would I do it again?

I’ve taken several road trips in a Mustang Mach-E lately, and wow, have I learned a lot.

At first, I was nervous to take the plunge into road tripping in an EV, especially driving a distance that exceeds the Mach-E’s range of 234 miles. Silly, I know; it’s the rare car that can travel 500 miles on a tank of gas, so why would we expect that of an EV?

But as range anxiety sets in, nerves flare up: what if the battery runs down faster than expected? What if I get stuck? Where are the chargers, exactly? What if they are broken or slow? Will I be able to get a soda or use the restroom? What if there are creepy people around?

All the goblins flooded my mind, but I had to remind myself: I can do this; lots of others have before me; I’m smart and capable.

This story is 100% human-researched and written based on actual first-person knowledge, extensive experience, and expertise on the subject of cars and trucks.

The Dirty Truth About EV Charging: It’s Not Conspiracy, It’s Complacency

As I set out I quickly discovered some of EV charging’s dirty secrets. Or maybe just un-fun realities that stoke fear around EVs. The roots of a lot of misinformation are not necessarily by design, but rather, by lack of vision, with each player in the equation mostly doing their part and leaving the customer experience to others, and that’s where it falls apart.

This also lets the insiders keep the tips and tricks a secret and doesn’t create a safety net or road map for newbies.

The end result is a network and process that can be difficult to navigate. But for the fun of driving an EV, the ability to charge at home and ultimately, saving money and being more efficient, it’s worth it.

READ MORE: What My 5-Year-Old Thought About Road-Tripping in the 2025 Rivian R1S

Need to Find a EV Charging Station? “The App Does it For You”

This is the first dirty little secret: EV apps, either a car’s built-in navigation or a phone-based app, decide when and where you should charge. It’s the answer that so many in the EV industry think is perfect for EV charging: let the app guide you to a charger so you’re never without juice. And it strips drivers of the most basic human right: To shop, and to pick, where and when you charge.

Built in navigation and apps can be flawed. Apps can take you to a charger next to a store’s dumpsters, to a location without light or hidden behind a building. The app doesn’t know you’re a woman traveling alone or that it’s dark.

It can send you to a lone charger in a location without other services, such as restrooms, a convenience store or vending machines. The car needs to recharge but you don’t get to do the same? I didn’t find many of these on my route but I know they are out there.

Apps, like the FordPass app which I’ve come to appreciate for the amount of information you can find about chargers, can do some helpful things: Ensure you get to an aptly powered terminal, that you’re not too far off your route, that there are available chargers and that they’re not broken.

Critics Say We Need Infrastructure, But Its There

If you drive the expanse of some of the most-traveled highways in the US you’ll see it all: signs for gas, for soda, beer, cigarettes, lotto, fast food, and often, all under one roof. You’ll see signs for retail stores, entertainment complexes, theme parks, historical destinations, parks, picnic areas, scenic overlooks.

What’s missing? No signs for EV chargers. Not one. Much less, price per kWh, which is essentially the price at the pump. It varies from about $.40 to about $.70 per kWh. And often the EV chargers are not visible from the road, so even just looking for chargers on your route can be challenging.

And get this: there are more than 180,000 public EV plugs in the us. Compare that to 145,000 gas stations across the country (so maybe 700,000 pumps? 800,000?). Neither are a small number and both mean that charging is out there, you just have to find it.

Longer Drives are Possible, and They Can Even Be Spontaneous

The lovely thing about a gas-powered car is you can go anywhere. EVs? Same. Go to the farthest reaches on earth and you’ll see a Tesla. That inspired me, though not seeing any signs for EVs made me nervous.

In hindsight, after my first road trip to Houston, I counted the number of DC fast charger locations (delivering 125+ kWh or more) along my route: 16. I could have stopped 16 times to charge the car.

Then, I counted the number of fast chargers between Charlotte and Charleston: 17. And between Austin and the exurbs of Dallas (really, south of Waxahatchie)? This was a surprise: 6. However, I question that number because I’m pretty sure I saw more than that, though I was relying on the PlugShare app to count them for me.

If I was headed someplace known to be remote, Big Bend National Park or Colorado’s Million Dollar Highway, I’d check on the plugs first to make sure I won’t get stuck.

A Lack of Advertising Keeps You From Shopping EV Charging

Shopping chargers isn’t something I’d thought of, really. And maybe it’s not the chargers I want to shop, but rather, a good Buc-ee’s experience, or a Tesla charger, a hot meal or a clean restroom.

You can shop chargers and rates using an app, of course, but you either have to do this before you leave, pull over and browse while on the road or rely on a passenger do to it for you. Some built-in interfaces allow you to choose your charging location, too, but with varying amounts of information.

Is a sign with a price too much to ask?

Rates Vary—and So Do Surcharges and Penalties

We like to know the price of gas before we start the pump; I’d love to know the price per kWh before I start charging, too. Prices range from $.30 to $.70 per kWh delivered to your car. I mostly paid in the $.40-$.48 range, costing about $15-$20 per charge to recharge about 50% of the battery.

A more expensive charger could double that amount, and it seems that pricing tends to be pretty similar by region; I found cheaper prices in areas with more chargers and higher prices in areas with fewer chargers.

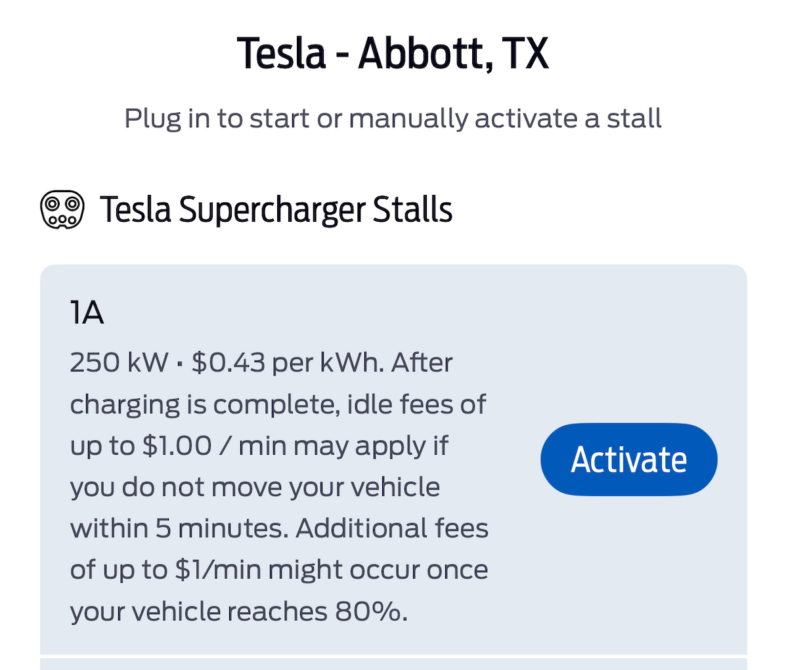

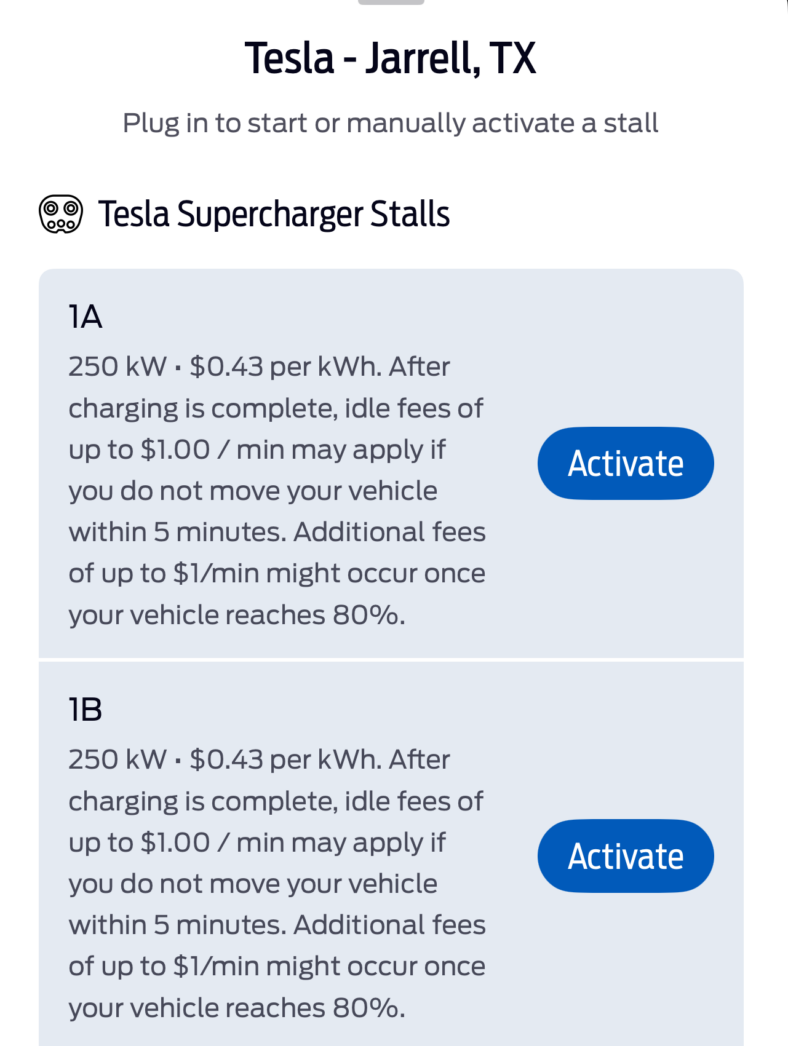

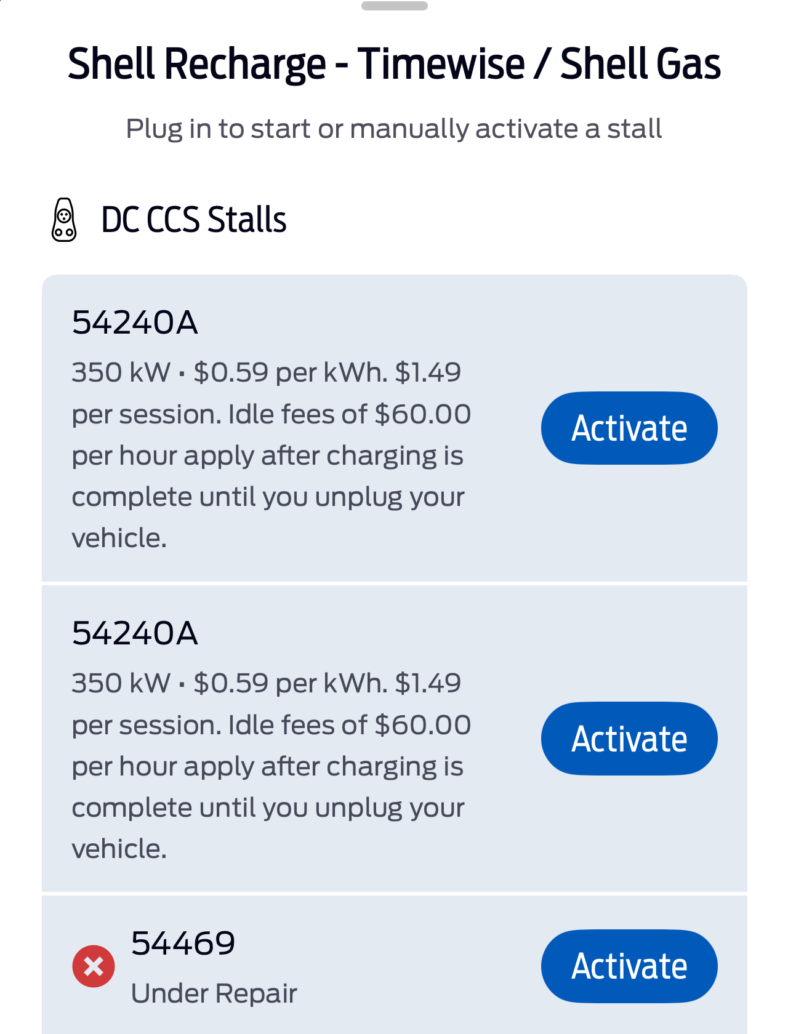

And then, there are the surcharges: a per-charge session fee of $1 is common, and so are idle fees that can run to $60 an hour after your car is done charging. Prices might also increase once your car reaches an 80% charge since that last 20% takes longer to complete. Some stations will charge you $1 a minute for that last 20% which can take half an hour or more.

All of these details can be found on the apps, and if you can read it, on the terminal (I find information on the terminals hard to read thanks to fogged plastic covers, small type and sun glare). It’s good to know what you’re getting into, and to pay attention; don’t walk away and have a long lunch. You may come back to a hefty idle penalty.

Broken Chargers Leave You Stranded: Fact or Fiction?

This has been a common complaint for years. And while yes, there are chargers that are non-functioning, the ones that are profitable are generally working, especially the higher-wattage chargers, those that deliver 125 kWh or more. I found using Plugshare, FordPass and A Better Route Planner showed me the broken chargers so I could avoid them.

And, not all non-working chargers are broken. Some just take longer to ‘handshake’ with the car, the credit card and the plug. More than once (in the past, not on this trip) I’ve had to move to another plug at the same charge station to charge the car, and it’s always worked.

Is it Worth Road Tripping In an EV?

Looking at the math to figure out if gas is really more expensive for a road trip is not as easy as it seems, but here it is. At home, I pay about .05 per kWh to charge the car (residents of Los Angeles pay $.07-$.13 per kWh, for comparison). Public chargers in my neighborhood are about $.48 per kWh, so of course, charing at home is preferable and possibly not even detectable on my power bill. Public charging is about the price of gas at $2.75 a gallon, which is about what it is in my neighborhood right now.

Looking at my monthly expenses to power the car, here’s how it breaks down and how it compares to buying gas:

- Home charging: 197 kWh @ $5.138 kWh = $34 to drive 560 miles

- Public charging: 175 kWh @ $.40-$.48 = $67.63 to drive 485 miles

- Total charging cost: $101.63

- Cost to drive a gas-powered car, assuming 22 MPG at $3.19/gal: $151.52

The Biggest Advantage? You Get to Decide What You Want to Pay

On my recent trip to Dallas my last charge stop was at Buc-ee’s in Temple TX, about 80 miles from home. I had about 40 miles on the range, so I charged to about 120 miles of range: enough to get home but not close to 200 miles, or 80% that is essentially equal to a ‘fill-up.’

Why didn’t I fully recharge the car? Because I could do that at home and pay half the price. That’s something special and something you can’t always do with gas, which is usually cheaper on the highway than it is in the suburbs. And even if gas was cheaper at home, it wouldn’t be as cheap as home charging is.

When Is an EV Not Worth It?

If you live someplace where EV charging is difficult, then it’s clearly not for you. If you live someplace where EV charging is more than about $.50 per kWh and you can’t charge at home, it may not make sense either.

But I was surprised to find that the chargers in my neighborhood can actually often cost less than the price of gas, though prices always seem on par with gas; the price per mile is similar.

For drivers looking to spend less than the price of gas, an EV doesn’t make sense if you can’t charge at home — even if you have to spend a little to add an outlet or upgrade your electric; you’ll earn it back over time.

However, if an EV is something you want, it can cost the same or less than a gas-powered car, so it really comes down to personal preference.

And When Is it Worth Absolutely Every Penny? This.

If you’re wondering why people love EVs, it’s instances like this. On my drive I found myself in afternoon traffic on the highway, among trucks, SUVs and then, a very loud Mustang GT, a 500 HP gurgling, growling beast of a car. The driver was curious about the Mach-E—I get a lot of that on the road, especially from Mustang drivers—and he pulled up beside me, revving the engine. I ignored him, accepting that there’s still a lot of curiosity about the Mach-E, and for good reason. It’s a great car.

But after a bit of the GT’s surging and slowing, I decided he really just needed to have his curiosity satisfied. So, when the road was clear, I floored the accelerator and shot past him. Before he even knew what happened, he was a dot in my rear view mirror.

What his Mustang lacked is what my Mustang boasts: Instant acceleration, which is the benefit of driving an EV. Even a mildly powered EV like the Mustang Mach-E, with about 290 HP, will toss you back in your seat in a flash. It’s fun and when you need it, it’s welcome.

And it’s what makes EV ownership, and figuring to the hidden details, worth it.

More About:Car Culture